Always on the Clock: Public Employees May Lose Pensions for Crimes Committed Outside Work

Submitted by New Jersey Criminal Lawyer, Jeffrey Hark.

According to the 2013 U.S. census, New Jersey has 131,542 public employees including judges, lawyers, corrections officers, and transit workers just to name a few. Many public employees look forward to the benefits of the Public Employees’ Retirement System. But, if you are convicted of a crime and it is found to even indirectly relate to your job, or ability to serve as a public employee, you may lose your pension and benefits. Getting these benefits back can be an unclear journey into a nexus of administrative and judicial review.

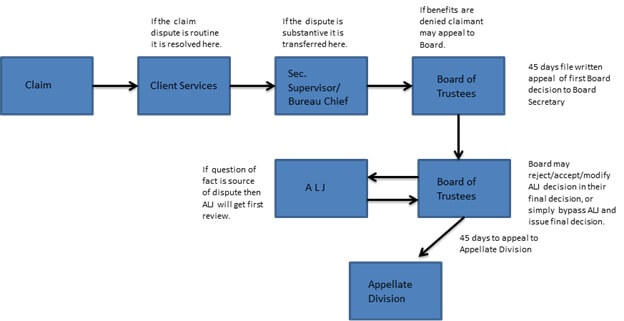

First I will provide a brief outline of pension dispute resolutions and appeals. Routine matters regarding pensions and retirement benefits are handled by the Division’s Office of Client Services, however when the dispute is not routine it is referred to the Section Supervisor/Bureau Chief. If the claimant is denied benefits or otherwise not happy with the Division’s decision then they may appeal to the Board of Trustees. Once the Board of Trustees issues a written decision, the claimant has up to 45 days to file a written appeal to the Board Secretary. This appeal is critical because if the 45 days run without an appeal the decision is final and may never be appealed again. Once an appeal is filed the Board of Trustees will either route the appeal to the Office of Administrative Law or the Appellate Division of the Superior Court. Questions of fact (versus questions of law) typically goes to the Office of Administrative Law to be heard by an Administrative Law Judge. However, even after the Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) makes a decision, the Board of Trustees may still reject, or modify that decision and then issue their final decision. In the case that a question of law exists without any factual dispute then the Board of Trustees will issue their final decision without an ALJ. Regardless of which route is taken, the claimant will again have 45 days to appeal the final decision by the Board of Trustees to the Appellate Division. Please see the below flowchart outlining what I have just explained:

What about the actual statute? N.J.S.A. § 43:15A-38 states in relevant part that :

Should a member of the Public Employees’ Retirement System, after having completed 10 years of service, be separated voluntarily or involuntarily from the service, before reaching service retirement age, and not by removal for cause on charges of misconduct or delinquency, such person may elect to receive:..

This underlined portion is triggered whenever a public employee is removed for cause on charges of misconduct related to their official duty. On July 1, the Appellate Division decided In re Jacalone, reiterating that any charges touching on the official duty of an employee invoke the N.J.S.A. § 43:15A-38 disqualification for retirement benefits based on removal for cause. This can be further illuminated by referencing N.J.S.A. § 2C:51-2(a)(1)-(2) which states a public employee shall forfeit their employment if:

- He is convicted under the laws of this State of an offense involving dishonesty or of a crime of the third degree or above or under the laws of another state or of the United States of an offense or a crime which, if committed in this State, would be such an offense or crime;

- He is convicted of an offense involving or touching such office, position or employment…

When examined using the plain meaning of the statute’s language, the fact the legislature distinguished “touching” from “involving” clearly demonstrates that a crime need not be directly related to the job duties of the public employee to cause him to forfeit that position, and this forfeiture would clearly trigger the limitations set forth in N.J.S.A. § 43:15A-38. While a crime that is completely unrelated to one’s job as a public servant may not amount to “touching” that employment, the courts have found conduct to touch employment even when the connection was not official. Such examples include a police officer who used his badge and gun during a road rage episode, and stalking between two public corrections officers outside of work. In the most recent case, Jacalone, a county sheriff’s office records clerk stole money from a professional association that was related to but not under the umbrella of her employer, and was denied benefits.

A court’s scope of review of an agency decision is restricted to decisions that are either arbitrary, capricious, or unreasonable based on substantial evidence. A long lineage of related case law has given reviewing courts precise points to use when determining whether an administrative decision meets this standard, including:

- whether the agency’s action violates express or implied legislative policies, that is, did the agency follow the law;

- whether the record contains substantial evidence to support the findings on which the agency based its action; and

- whether in applying the legislative policies to the facts, the agency clearly erred in reaching a conclusion that could not reasonably have been made on a showing of the relevant factors.

The main grounds for limited judicial review of agency decisions is the fact agencies possess a particular expertise in their given domain that is not shared by the courts, and therefore should not be usurped.

In summary, if you are a public employee and you commit a crime the odds are not in your favor for keeping your hard earned retirement benefits. But, if the crime is completely unrelated to your job and does not put your honesty into question, then you may have a chance on appeal.